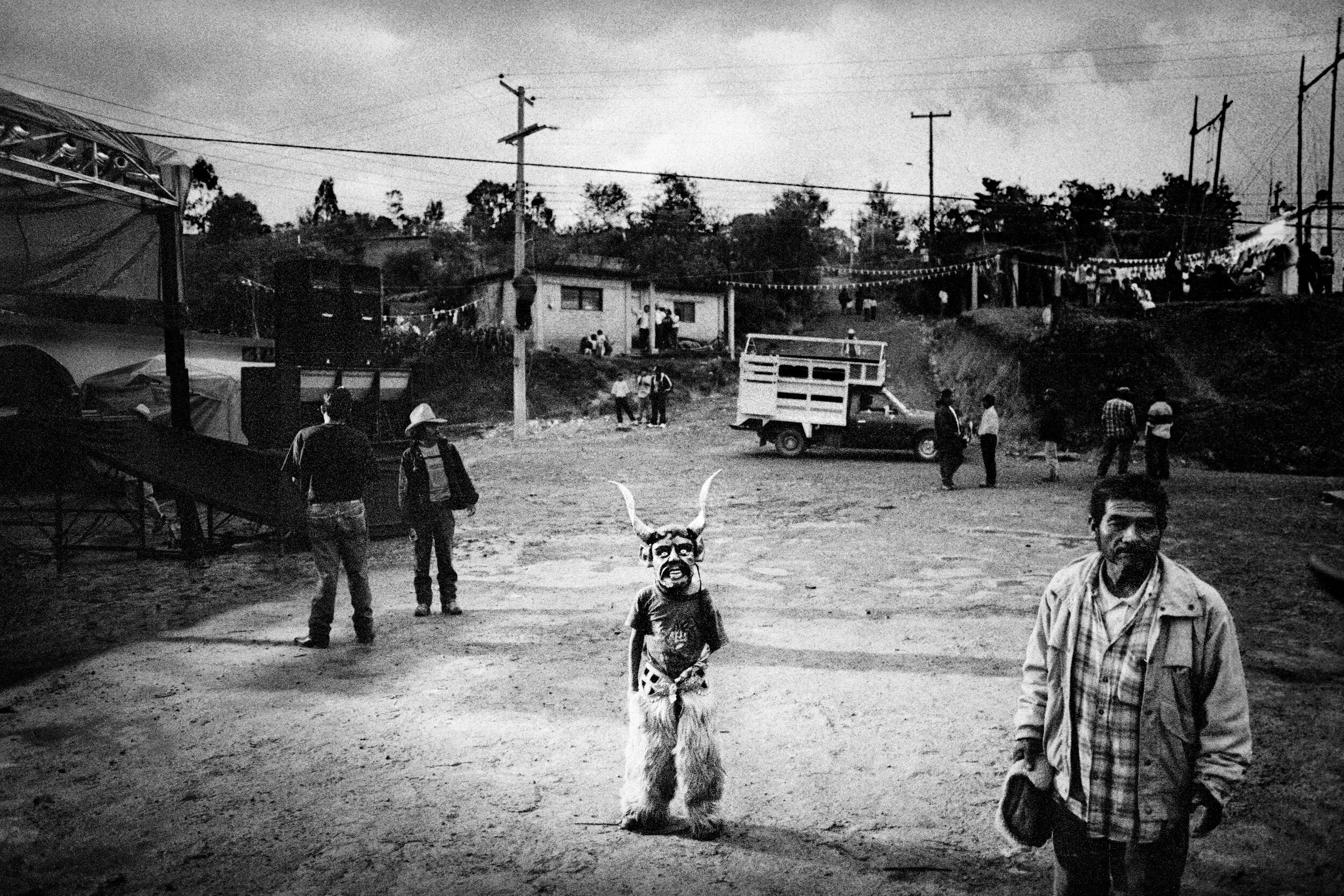

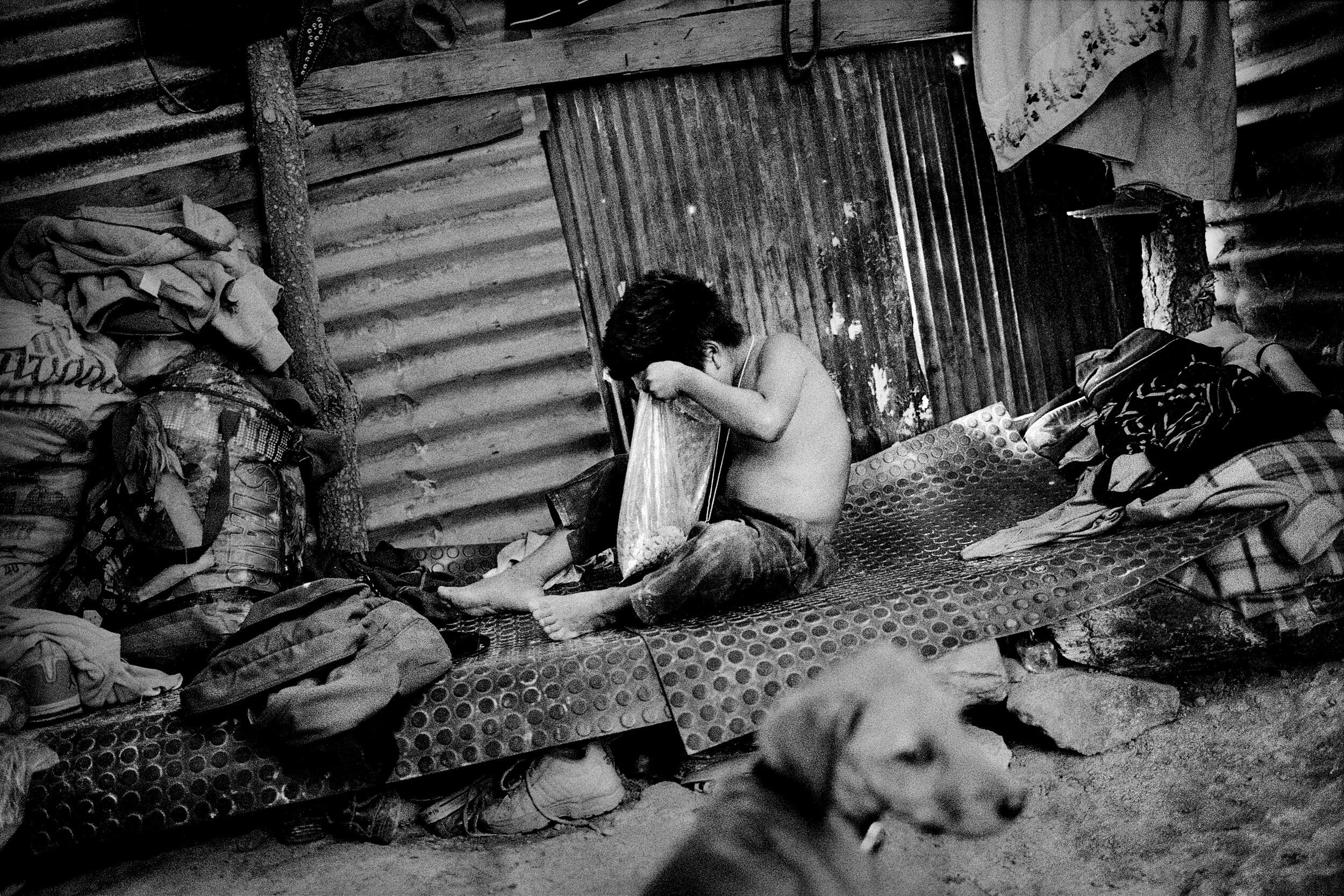

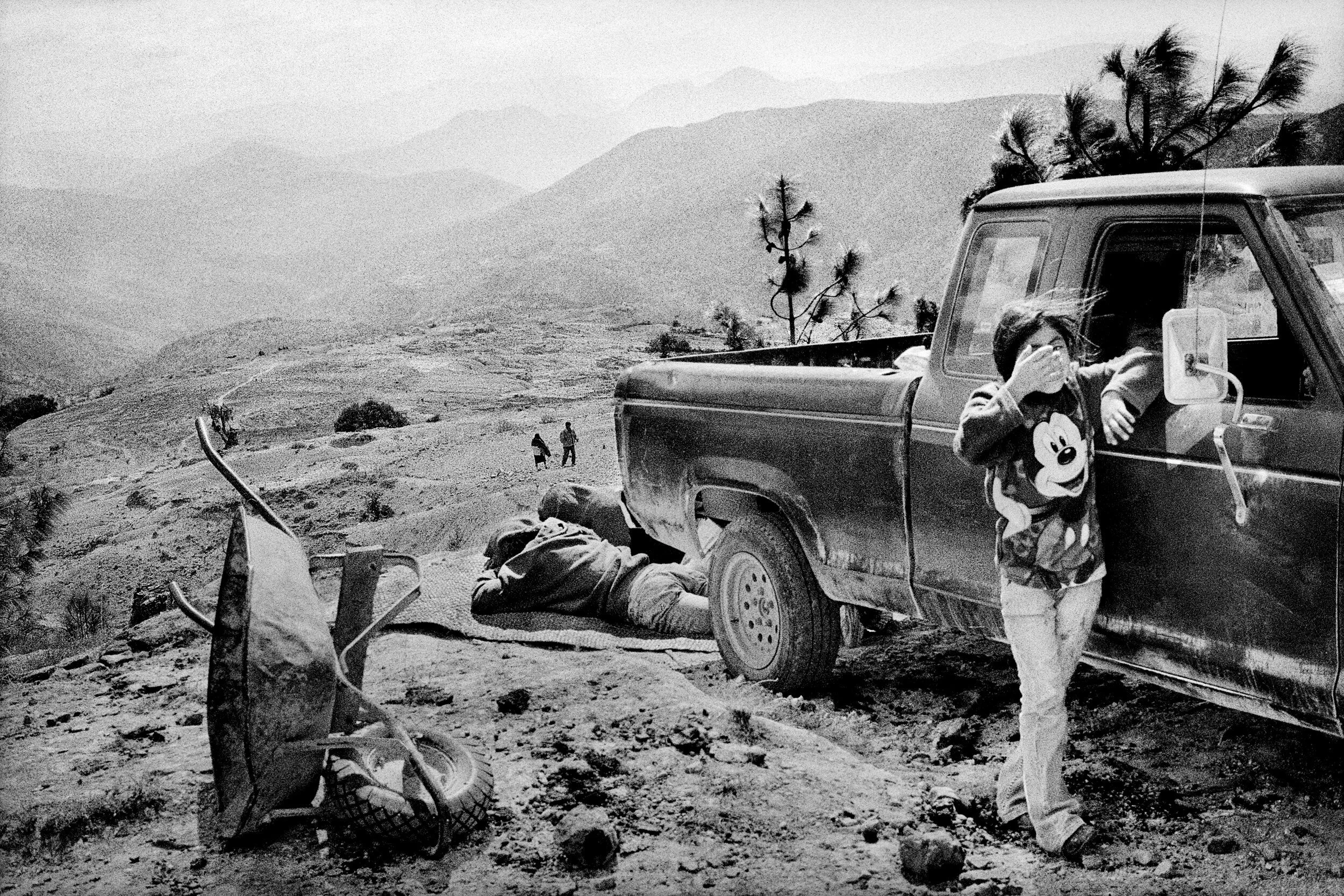

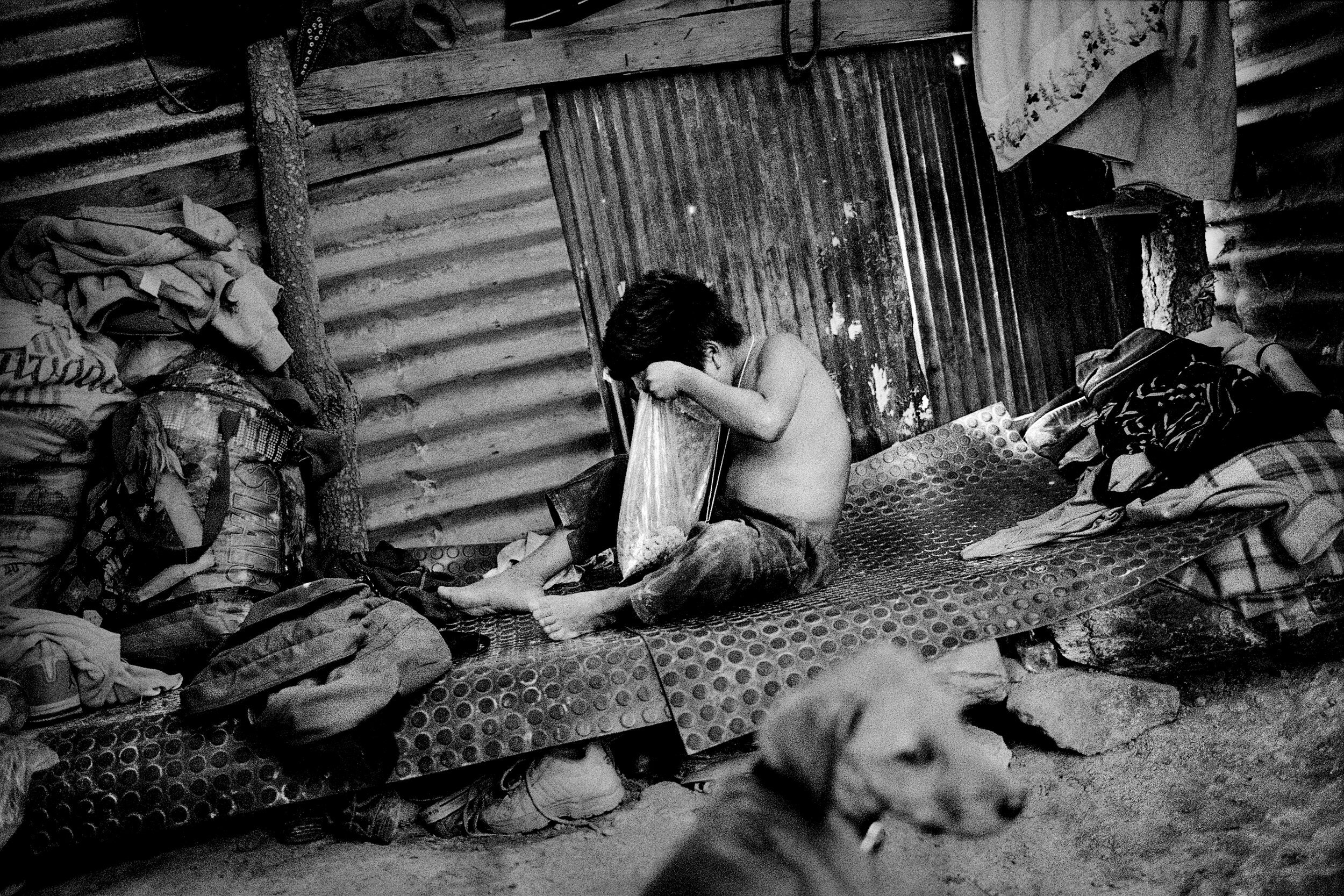

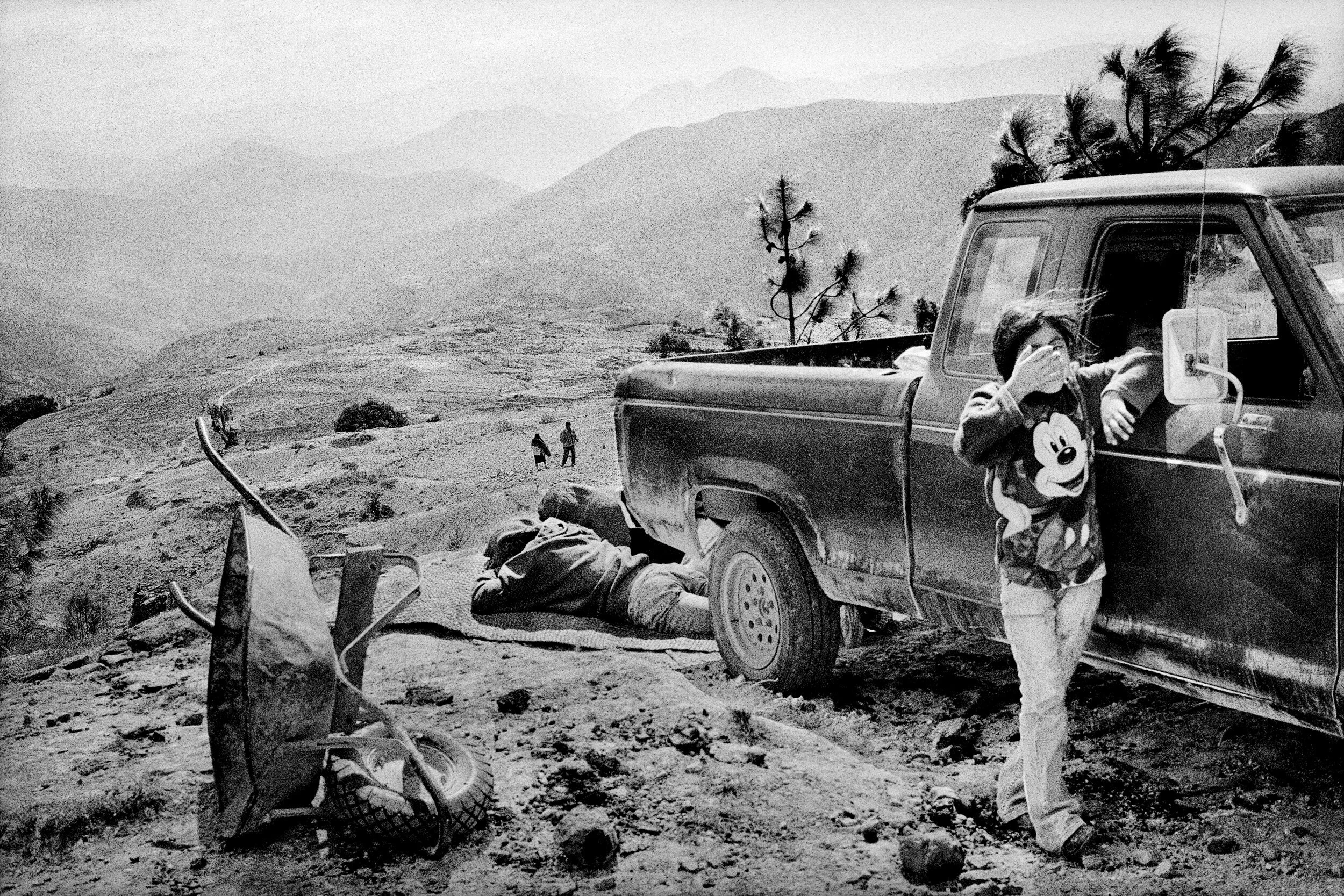

As Black photographed communities in California, he noticed a change among the people working in agriculture. While the fields have always served as a stepping stone for migrants and immigrants, documented and undocumented – starting well before the Great Depression’s “Okies” and “Arkies,” and including Chinese, Filipino, Armenian, Indian, and Spanish-speaking people from Mexico – Black observed a new group, indigenous immigrants from Mexico who speak only Trique, Mixtec, or Nahuatl. Visiting one worker’s home, unable to understand the family’s language, Black learned the family was from Oaxaca, MX. Encountering deep prejudice even from other Mexican workers in the US and largely living in grinding poverty, indigenous immigrants were often exploited in the fields. Black wondered what had driven the families to leave home. He embarked on what became dozens of trips to the mountains of Oaxaca, where he saw an ancient way of life crumbling: in the birthplace of corn cultivation thousands of years ago, where in the 1960s scientists had introduced new farming techniques, communities were suddenly seeing landslides, withering crops, and anyone able to work following opportunities in the US, leaving old women, men, and children behind to maintain dwindling villages increasingly preyed upon by drug cartels. Against this backdrop of environmental catastrophe and economic violence, Black produced such photo essays as “The People of Clouds,” “After the Fall,” and “The Monster in the Mountains.”